|

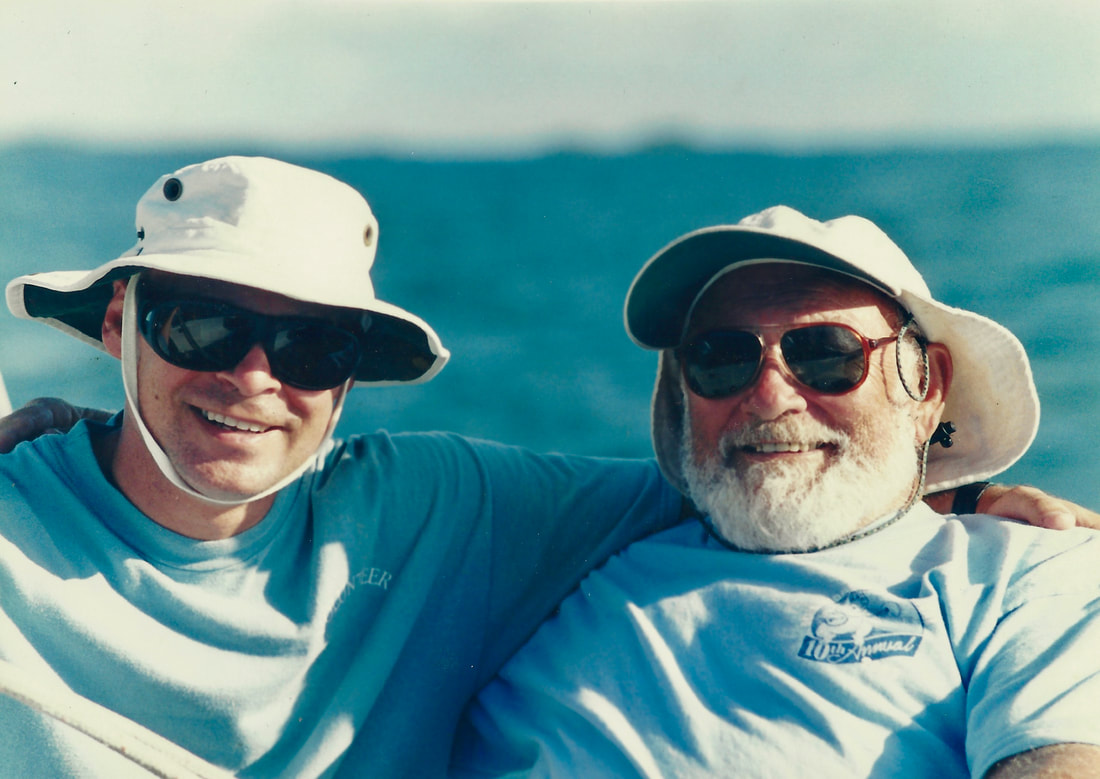

My late dad, the Great Bob Millard, never really planned for retirement—yet he actually had more money after he retired than he ever did while he was working. On the other hand, I have a friend (call her Deb) who did do some saving, but she’s still working well into her so-called Golden Years—because she needs the paycheck.

The reason? Dad was more or less forced to save, while Deb was mostly on her own. That’s because Dad was part of a defined benefit retirement plan while Deb had a defined contribution plan. The two terms may sound esoteric, but if you’re in your working years, you ignore them at your peril. For much of the 20th Century, millions of Americans worked for companies or other entities with defined benefit plans. Such plans are typically referred to as pension plans, and nowadays they’re almost exclusive to government entities and a few extremely large corporations. Here’s how they work: My dad was an administrator at the South Carolina School for the Deaf and the Blind. As such, he was an employee of the South Carolina government and was required to participate in their defined benefit retirement plan. Under the plan, a certain percentage of the employee’s paycheck is taken out and added to the overall state retirement fund. That giant fund is invested and managed in such a way that it funds the retirements of all participant retirees. Here is how it looks from the employee’s perspective: You work for the entity for 25 or 30 years, contributing to the retirement fund with every paycheck. This happens automatically whether you plan for it or not. The state contributes as well. Upon retirement, you’re guaranteed a certain percentage of your ending salary based on a formula—typically 60% of the highest salary earned. This is a gross oversimplification in several ways, but you get the idea. The new retiree is guaranteed an income for life, complete with cost-of-living increases to keep up with inflation. In Dad’s case, the state of South Carolina was on the hook: if the state retirement fund ran a little short, the taxpayers would have to cough up the difference. Defined benefit plans are the norm for governmental entities, and they were once common at most large corporations. But they fell out of favor a few decades ago as corporations began shifting the burden of retirement to employees. Under a defined contribution plan, each employee decides how much to save toward their own retirement—and also where to invest that money. Your retirement lifestyle will depend on how much you can accumulate before they give you the proverbial gold watch. Unfortunately, most folks don’t save nearly enough. For the most part, we spend what we make on food, clothing, shelter, cars, taxes, college for the kids, and the occasional vacation. In the 21st-Century economy, that doesn’t leave a lot to set aside for retirement. You may be wondering about Social Security. It is separate and apart from your retirement plan, so most people will collect it regardless. But Social Security is not a retirement plan--just a stopgap to keep seniors out of poverty. To make things worse, financial education is pretty much nonexistent in our schools. And the business models of most financial advisors focus on clients who already have built substantial wealth, which means that Americans with the greatest need for sound financial advice—those in their prime earning and saving years—are pretty much on their own. Fortunately, this problem is beginning to be addressed by a new generation of financial advisors focused on helping younger earners and their families. It breaks my heart to say that if you are one of those older workers who sees no way to retire, I probably don’t have a lot to offer you. But each situation is different, so it might make sense for you to talk with a fee-only financial advisor to explore whatever options you might have. So, how could my dad have had more money in retirement than when he was working? For one thing, he and Mom (also a SC state retiree) had less in the way of expenses. Their four kids were finally grown up and self-sufficient, their house was finally paid off, and their retirement checks automatically rose each year with the cost of living. So despite the fact that their careers didn’t make them rich, their retirement was secure and happy. They also had the satisfaction of knowing that they'd helped thousands of young people make their way from childhood to adulthood. That’s a form of wealth you can’t put a price on. If you’re young and just getting started, those are two good reasons to consider becoming a teacher. Andy Millard, CFP® is a retired financial planner and former principal of Millard & Company, an investment management firm. He does not offer financial planning services; this column is not intended as advice but rather education, commentary and opinion. Consult a professional advisor. If you have general questions about financial planning or investments, feel free to submit them to Andy at [email protected].

2 Comments

Many folks have mixed feelings about investing. On the one hand, they know that investing in stocks or mutual funds may be the best way for them to finance a comfortable retirement or put their kids through college. But on the other hand, they might not feel all that great about some of the companies their investment dollars support.

Maybe they've read that a particular clothing manufacturer employs child labor in unsafe factories in some far-off corner of the world. Perhaps another company produces high levels of toxic waste. Another might be less than forthcoming in the way they report their profits. Our hypothetical investor might wish to avoid investing in the stocks of those particular companies. On the flip side of the coin, this investor might have a desire to actively support other companies, such as those involved in producing clean energy or whose board of directors includes a high proportion of women and minorities. Over the last few years, more and more investors have become vocal about seeking such options, and a market has arisen to meet the demand. The phenomenon is known as ESG investing. "ESG" stands for environmental, social, and governance. In a nutshell, this approach tries to avoid investing in companies deemed to have a negative impact in those three areas, and favors companies that try to make the world cleaner, kinder, more diverse, and more sustainable. Here's a quick look at each factor: The Environmental area deals with sustainability. It considers such factors as air and water quality, clean energy, natural resource conservation, waste management, and hazardous materials. The Social area deals with humanity. It looks at labor practices, health care, education, housing, and community involvement. The Governance area deals with corporate ethics. It examines pay equity, executive suite diversity, shareholders' rights, accounting transparency, and the makeup of companies' boards. As you can imagine, this is a new and rather loosely defined discipline. There are no hard and fast rules defining what does and does not qualify, so you need to look carefully at the options—and there are a lot of them. The most common way to participate in ESG is through a mutual fund or ETF (exchange-traded fund). The differences and similarities of mutual funds and ETFs are not important to this discussion, so we’ll set them aside for now and concentrate on the ESG filters. Consider a hypothetical ESG-focused mutual fund. It might be exclusionary, meaning it filters out companies it considers to be especially egregious in certain ESG areas—or it might be inclusionary, meaning it actively seeks to identify and include companies that are leading the way in a respective ESG discipline. It may focus on only one factor—environmental, for instance—or incorporate all three. Even though ESG investing is a relatively new strategy, hundreds of mutual funds and ETFs utilize its principles to some extent or other. More ESG vehicles are popping up all the time. But like all strategies, there are some limitations and special considerations. Most of the concerns arise from the newness of the concept. Definitions of what constitutes ESG investing are not always consistent among fund managers, which can lead to considerably different approaches. Rapid growth in the ESG space has led to a plethora of options, many of which have a small asset base and a short or nonexistent trach record. Then there’s the diversification issue. Most investors diversify as a way to reduce market risk: they buy lots of different companies in lots of different industries. But ESG funds purposely limit the list of companies in which they invest, which can potentially decrease diversification and lead to a dilemma for investors who want both diversification and ESG filters. In other words, as with any area of investing, look closely and learn as much as you can before committing your hard-earned money. This column is not intended as advice but rather education, commentary and opinion. Consult a professional advisor. If you have general questions about financial planning or investments, feel free to submit them to Andy at [email protected]. “That’ll be $326.12, please.” Such was the damage from my last trip to the supermarket.

But wait, there’s more! The next day I went to our local farm store, where we buy locally produced meats, veggies, jams, and other sundries, along with fresh NC-caught seafood. Total bill there: $270.32. Have you ever stopped to think how much you actually spend on food? I certainly hadn’t. Then I volunteered to take over the grocery-buying duties during the COVID-19 crisis. As I was putting up the last of the foodstuffs that day, it struck me that this would be the perfect time to assess how much we really spend on food and drink. The total between those two trips was just shy of $600. $600 for groceries? For two people? That’s a lot, right? Let’s see. During the pandemic, my wife and I completely stopped consuming any food that was not prepared in our own kitchen. No dinners at local restaurants. No lunches from Nana’s or Waffle House or the fast food joints, no pizzas from Sidestreet or the Brick. For the time being, 100% of our food is bought at the store and prepared at home. We decided that this is the most responsible course for us, and we're just now starting to ease up on it. There are, of course, very real downsides to this approach — most significantly, downsides to the businesses that need and deserve customers. But there is at least one upside. Now we can really see how much it costs to eat. I probably should have mentioned that we have a system whereby I buy groceries once — and only once — every three weeks. So the food from those two trips will feed us for the next three weeks. That works out to $200 a week, or $100 per person per week. Taken a step further, at three meals a day, we’re spending an average of $4.76 per meal per person. That doesn’t sound too far out of line, does it? And it covers everything we ingest: every morsel of food and every drop of liquid. For comparison, a Quarter Pounder with cheese Extra Value Meal at McDonald’s costs $5.79 plus tax. (source: fastfoodmenuprices.com) If you’re like most folks, your home-cooked dinner habits are probably nothing fancy: pork chops, chicken, burgers on the grill, spaghetti, an occasional sirloin. Our biggest extravagance is the seafood we get from the Farm Store. Consider the national average. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the average two-person household spends $151.25 per week on food. That’s a little less than my particular two-person household, but I suspect it’s an underestimate. What about alcoholic beverages consumed at home? Drinks at the local pub? Snacks at the convenience store? Quick trips to the ice cream shop? That stuff adds up quickly. Then there’s the category commonly referred to as dining out. Those who do go out may spend less at grocery stores but more at restaurants — probably a lot more. That’s the budget killer that most people never fully understand. According to MoneyUnder30.com, the average commercially prepared meal costs around $13. We all know how easy it is to spend more than that, especially when you add drinks, a tip and the cost of traveling to the restaurant and back. (source: www. MoneyUnder30.com) So depending on your situation, $100 per person per week is not unreasonable. Is it any wonder, then, that so many among us struggle so hard just to put food on the table? Over 25% of children live in food-insecure homes, according to the Southeastern University Consortium on Hunger, Poverty and Nutrition. To make matters worse, the less a family spends on food, the lower the nutritional quality of the food they’re likely to buy, increasing the chance of negative health consequences. This may be a good time for you to examine your own food spending. If you’re locked down to the extent we are, it should be easy. If you’ve started going out, the task is more difficult but still doable. Don’t cheat — count everything. See where you stand and where you can improve. And don’t forget to count your blessings. This column is not intended as advice but rather education, commentary and opinion. Consult a professional advisor. If you have general questions about financial planning or investments, feel free to submit them to Andy at [email protected]. Photo by Nicole Michalou from Pexel I’ve known many folks who would never carry a grudge against someone else, but they just can’t seem to get over being mad at themselves. As often as not, it’s about money.

What's the worst financial decision you ever made? Over the years, many clients have shared their regrets with me, and they often leave me shaking my head. A lot of so-called bad decisions aren’t actually that bad—or aren’t decisions at all. William H. Walton wrote, “To carry a grudge is like being stung to death by one bee.” This quote reminds us that clinging to anger is self-defeating. Every time you renew your anger, it’s as if you’re pulling a pet bee out of your pocket and inviting it to sting you again. A common regret goes something like this: "I should have sold Intel when it started going down." Or: "I could have bought Tesla at $30 a share." But I don't think those are bad decisions so much as they are a failure to accurately see the future. And who can do that? You hear other regrets, such as: "Why did I start that business?" Or, "Why did I throw good money after bad?" Or, "Why did I take that dead-end low paying job?" But again, those all involve an inability to see the future, which nobody can do. Did you make the best decision you could at the time, knowing what you knew at the time? Of course you did. So, I say don't let it bother you. Here’s another category that does qualify as a mistake. It involves a failure to stop and think about what you’re doing when you’re doing it. But here again, these are not reasons for regret so much as opportunities to learn and grow. Remember how your high school math teacher used to chide you for making careless mistakes? Well, I think that's a good way to describe most true financial blunders. You eat out too many times a week without thinking about it. You buy stuff that you never use, or clothes you never wear. (I'm guilty of that.) You run up your credit card bill because it's easy. These are real-time decisions that you can do something about if you just pay attention. The worst financial decision of all is a failure to plan ahead. Try to look down the road 10, 20, 30 years. A small decision today, a small course correction, can have a huge impact in the long run. The challenge here is that it's so easy to ignore the future because the present demands all of our attention. Although we can't really know the future, we can try to plan for it. Dwight Eisenhower said, "Plans are worthless, but planning is everything." When it comes to money, how true that is. This column is not intended as advice but rather education, commentary and opinion. Consult a professional advisor. If you have general questions about financial planning or investments, feel free to submit them to Andy at [email protected]. You’ve no doubt heard about the five stages of grief. But did you also know about the six phases of retirement? I bet you'll agree that it makes perfect sense.

This information came to me through an excellent continuing education course entitled “Effective and Ethical Communication with Seniors.”* The highlight was information surrounding how individuals make the adjustment from career to retirement. If you’re retired, there’s a good chance you’ll recognize some of your own experience here. I’ve certainly seen it reflected in the lives of friends and clients as well as my own parents. There’s no specific time period for any one phase—a person may zip through one phase but linger in another—but most retirees will experience all of them. Phase 1: Honeymoon. You’ve probably been looking forward to this moment for years. Now that the day has arrived, you’re free. You can take that extra-long cruise, work on that home handyperson project, learn how to sculpt, go fishing on a Tuesday. Far from sitting in a rocking chair, you might be at least as active during this early phase of retirement as you were on the job. Phase 2: Rest and Relaxation. Once you’ve gotten through some of those long-postponed activities, you’re likely to be ready to take it easy for a bit. Without the pressing need to get something done right now, you can sit back and allow your mind to make the adjustment to your new life. Part of that adjustment is simply pondering all that has brought you to this point. It’s almost an extended form of meditation: you just sit and allow yourself to be. Phase 3: Disenchantment. If you’re like most of us, you can only sit and think for so long. This is the disenchantment phase. Up to now, you’ve had a purpose—perhaps many purposes—driving you to get up every day and perform particular tasks or activities. But now you wonder: what’s next? You might start to experience limitations on your spending or your health. Perhaps you’ve moved to a new community. You realize that the adjustments you’re making are permanent, and that realization can throw you for an emotional loop. Phase 4: Reorientation. You’re not likely to wallow in disenchantment forever. Almost inevitably, you’ll reorient yourself to your world as it is now. You start to make adjustments, see new possibilities, recognize that there’s more living to do. You discover that this new life, though different from the life you’re used to, has its own rewards and opportunities for fulfillment. Reorientation can take many forms, and it can happen more than once. My dad got remarried ten years after Mom died. In my local community, many retirees join civic clubs or take up gardening or artistic disciplines. My Grandpa Percy Turner—the self-styled “Unmerciful Percival”—actually became an avid baseball fan late in life, a development that astounded anyone who had known him well. Phase 5: Retirement Routine. Your new reality becomes your new normal. I think this phase is more or less inevitable; after all, we humans crave a routine. For many of my retired friends, their routine involves attendance at meetings of the Kiwanis or Rotary Club, volunteering regularly with a local nonprofit, or a weekly meal with friends at a favorite restaurant. Walk into our local coffee house or McDonald’s on any given (non-pandemic) morning, and you’re likely to find a gaggle of retirees contentedly commiserating over a simple meal or cup of coffee. Similar rituals play out daily at retirement communities. These scenes are a joy to behold. Phase 6: Termination. Nothing lasts forever, of course, and that includes retirement. Unavoidably, you will face the termination of your retirement. Termination. It feels so harsh, doesn’t it? There’s no way to sugar-coat it. I suppose one reason we worry about the end is that we have no way of knowing how it will come or what it will be like. I don’t know about you, but I take comfort in the wisdom I’ve received from many, many older friends. As they’ve progressed through the six phases of retirement, most are content with who they are, the journey they’ve traveled, and their place in the world. Most will tell you that retirement has been another of the precious seasons of life, and that they are at peace with whatever the next season holds. May each of us be able to say the same. *”Effective and Ethical Communication With Seniors” available through WebCE.com. Photo by Monica Silvestre from Pexels This column is not intended as advice but rather education, commentary and opinion. Consult a professional advisor. If you have general questions about financial planning or investments, feel free to submit them to Andy at [email protected]. At any given time, I've served as financial steward for dozens of families. That kind of responsibility tends to focus the mind. Tote that weight around for a couple decades, and you find yourself thinking about everything in terms of risk and reward.

How much risk are you willing to accept in exchange for a possible reward? How great does the reward have to be to make it worth the risk? That’s how we should look at every single decision during this pandemic: risk versus reward. Simple personal choices carry major ramifications. Should I go to work? To the store? Out to eat? Order food delivery? Get a vaccine? Wear a mask? Fly on a plane? Take a trip? Have friends over? Go to church? Attend a meeting in person? In today’s climate, these decisions carry at least as much weight as those advisors make for clients. In this case, you are your own client, and what’s at stake is not only your financial security, but also your life and health—not to mention the life and health of those you love—and even people you may never meet. Like I said, that kind of responsibility tends to focus the mind. Take it seriously. None of us can duck this responsibility. Like it or not, my choices affect you and yours affect me. Such decisions affect us in three areas: (1) health and wellbeing, (2) money and economics, and (3) our freedom to do as we please. Furthermore, each category has both a personal component (applying only to yourself) and a collective component (applying to your family, your community, and society as a whole). That makes six things you need to consider in order to make a sound decision. It would be dangerously irresponsible to ignore any of them. The task is made harder by incomplete information in regard to the disease and its emerging variants as well as the accompanying economics. There’s so much we still don’t know about this virus. Is it a lung disease or a blood disease? If you get it and then recover, do you become immune? If so, for how long? Can it cause permanent damage to your body systems? How dangerous is it to children? Can you get it from surfaces? How long does it linger in the air? How long do the vaccines last? Can we be sure a vaccine won’t have long-term side effects? There are other unknowns. How badly are people suffering from not working? How do closed schools affect students’ long-term development? How does working from home affect everything? How many businesses will fold under the strain? How long will it take to recover economically? Fortunately, there are some things we do know. Masking helps to prevent the spread. Social distancing works. Large gatherings are dangerous—for now. Brief contact is better than extended contact. Outdoors is better than indoors. How can you make sound decisions in this confusion? Start by trying to determine both the best and worst possible outcomes of the choices you face. Say I’m deciding whether or not to wear a mask. Worst case if I wear it: my face gets hot and itchy, and some folks may scoff at me for living in fear. Best case if I wear it: I help prevent someone else from getting sick—maybe very sick—and possibly spreading the virus to others. Should be an easy decision. Some others, not so much. Here’s a pro tip: Whenever I find myself in a high-stakes decision with a lot of unknowns, I focus more on the risks than the rewards—especially if the decision is being made for someone else. If I don’t fully understand the risks, I assume the worst and decide accordingly. I don’t want to place another person in danger because of a poorly considered decision on my part. But hey, that’s just me. This column is not intended as advice but rather education, commentary and opinion. Consult a professional advisor. If you have general questions about financial planning or investments, feel free to submit them to Andy at [email protected]. Photo by Yaroslav Danylchenko from Pexels Many folks hesitate to seek help from a financial advisor, for one simple reason: they don’t know what they don’t know. And they have a sneaking suspicion that what they don’t know might hurt them. Even if you’re currently working with an advisor, you may harbor some nagging doubts. After all, the reason many folks come to an advisor in the first place is that they’re unsure of how best to deal with money. The advisor clearly has the upper hand. The following three questions should help you level the playing field. They’re simple and straightforward. Every client should ask them of their financial advisor. Question 1: How are you compensated? It might feel tacky or unseemly to ask such a pointed question of a respected professional, but ask it anyway. And don’t stop asking until you have a complete answer. Financial advisors get paid in one of two ways: commissions or fees. Commissions come from providers of financial products, such as mutual fund or annuity companies. Commission-paying products are known as “load” products; they almost always carry higher internal expenses than no-load products. Fees, on the other hand, come from the client. Generally, they’re more transparent and straightforward than commissions. The most common method of fee payment is a direct deduction from your investment account(s). Under this system, the advisor is expected to seek out lower-cost investment products for the portfolio. Some advisors call themselves “fee-based.” That almost always means that the advisor receives both fees and commissions. A “fee-only” advisor does not accept commissions of any kind. There are competing interests in any advisor/client relationship. Strictly speaking, the client’s interest is to pay as little as possible for the best service. But an unethical advisor might be more interested in their own compensation than their client’s well-being. Indeed, more than a few former “advisors” have spent time in prison for fraud and other crimes. Fees imply that the advisor’s loyalty belongs to the client, whereas commissions imply loyalty to the product. But fee-only advisors aren’t conflict-free. Since they’re usually paid a percentage of the assets they manage, a fee-only advisor could be tempted to try and gather up all of the client’s money whether it’s appropriate or not. Question 2: How much will you personally make from your relationship with me? Knowing how the advisor gets paid is a start. Now you need to know how much. Do not shy away from this question; it’s a vital piece of intelligence that you deserve to know. The advisor may not have a precise answer the first time you talk with them. But—and forgive my indelicacy here—by the time you’ve discussed the full scope of your project and the advisor has some semblance of a plan for you, you can be sure that they know the number. At this point, “I don’t know” is not an acceptable reply. Maybe they just don’t want you to know. Most fee-only advisors will be able to answer this question off the top of their head: it’s probably a straightforward percentage of the portfolio they manage. (According to Investopedia.com, the national average rate is about 1% of the account per year.) BONUS QUESTION: Do you receive free travel? The question may seem odd, but the answer will tell you a lot. Early in my career, various mutual fund and annuity companies flew me and other advisors to New York City (where we enjoyed a gourmet dinner and tickets to the Yankees), New Orleans (fancy hotel, food and drinks in the French Quarter), and Washington, DC (luxury box seats for the Washington Football Team). If you think those companies expected something from me in return, you’re right. I felt the pressure, and it made me feel dirty inside. I stopped accepting such offers, and eventually they stopped coming. I felt a lot better about myself and my priorities. These kinds of junkets have gradually died out over the years as investment product providers have evolved, but many brokerage firms still provide luxury vacations as a reward for reaching sales goals. Who pays, you ask? Sometimes those same product providers sponsor the trips; it just passes through the firm first. You deserve to know about it. You may squirm while asking these three questions, but any ethical advisor should welcome them. If they hesitate, obfuscate, or try to change the subject, it’s a red flag. You might just want to keep looking. This column is not intended as advice but rather education, commentary and opinion. Consult a professional advisor. If you have general questions about financial planning or investments, feel free to submit them to Andy at [email protected]. Photo by Karolina Grabowska from Pexels

Despite what you've heard, your home might not be a financial asset at all—and it could even be a liability. It qualifies as an asset only when you're willing to sell it. Until then, it’s just a place to live. This goes double if you have a mortgage.

Think about it. If you have a mortgage, you technically own the house, but just miss a few payments, then see how that goes over with the bank. A person in that situation will quickly find out who really owns the place. But wait, you say, I don’t miss payments. That’s good. But the house still might not be an asset. Even if you’ve built some equity, you’re still obligated not just to the mortgage but also to the cost of taxes, insurance, and upkeep. Throw in the fact that many homeowners make it clear that they don’t ever intend to sell their house, and that house ceases to be a financial asset and becomes a place to live. To be sure, having a place to live is valuable—especially if your mortgage is paid off. Anyone who has made their final house payment will tell you there’s real value in that feeling of security. But unless you’re willing to actually sell it, the financial value of your house cannot be actualized. Even if it’s paid off, you still have those ongoing expenses. If, on the other hand, you ARE willing to sell the house, its financial potential gets unlocked and it becomes a powerful asset. Many folks use this strategy in retirement: with kids out of the house, a smaller place makes sense both financially and practically. I’ve known working people who became well-off through a combination of early home ownership and long-term serendipity. One client couple lived and worked in California, paid off the mortgage on a modest home in that state, then sold it upon retirement and moved to Tryon. Taking advantage of the much lower home prices in western North Carolina, they were able to buy a nice house here and invest the remaining proceeds, thus funding a comfortable retirement. Another client watched for decades as the family homestead gradually became surrounded by urban sprawl. She hated the idea of selling, but she almost had no choice; what was once a quiet country farm was now engulfed by shopping centers and apartment complexes. The millions she reaped from the sale was at least some consolation. You probably know of similar stories. What they all have in common is that the owners were willing to sell. I had another client in an almost identical situation to the one above. In this case several family members shared ownership, and no one could agree on what to do. What might have been a valuable asset became a long-term financial burden because of property taxes and other costs. What is it that prevents some folks from unlocking their home’s financial potential? For some, it is emotion and sentimentality. As a sentimental fool myself, I totally get this. Maybe you raised your kids in this house. There may be a doorway with pencil marks denoting their growth milestones. Beloved family pets may be buried in the yard. Who can blame you for wanting to stay? Then there’s the hassle of packing up and moving. Just this morning, I visited with a neighbor couple who were moving the last of their possessions from their Florida home of 30 years into their new home in Columbus. The wife told me it was the hardest thing she’d ever done, not from the emotional standpoint but simply because of the sheer effort of dealing with 30 years of accumulated stuff. Nevertheless, practicality might win out in the end. For years, one client ignored pleas from her grown children to sell her beautiful home so she could move to a retirement community. Eventually, the swimming pool turned green, the basement got moldy and the guesthouse roof started to collapse. After exhausting all her other resources, she finally sold for about half of what she could have gotten a few years earlier. There is one alternative to selling: the reverse mortgage, which we covered in an earlier column. This option has its own pitfalls, but it may be worth considering. Bottom line: The only way your home can be a financial asset is if you treat it like one. Start by paying off the mortgage—I firmly believe that no one should enter retirement with a house payment. And although it’s hard to do, try to remove the sentiment and emotion surrounding your home. If you can’t do that, then recognize it for what it is—home sweet home—and be grateful for it. This column is not intended as advice but rather education, commentary and opinion. Consult a professional advisor. If you have general questions about financial planning or investments, feel free to submit them to Andy at [email protected]. |

AuthorAndy Millard, CFP® Archives |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed