|

My late dad, the Great Bob Millard, never really planned for retirement—yet he actually had more money after he retired than he ever did while he was working. On the other hand, I have a friend (call her Deb) who did do some saving, but she’s still working well into her so-called Golden Years—because she needs the paycheck.

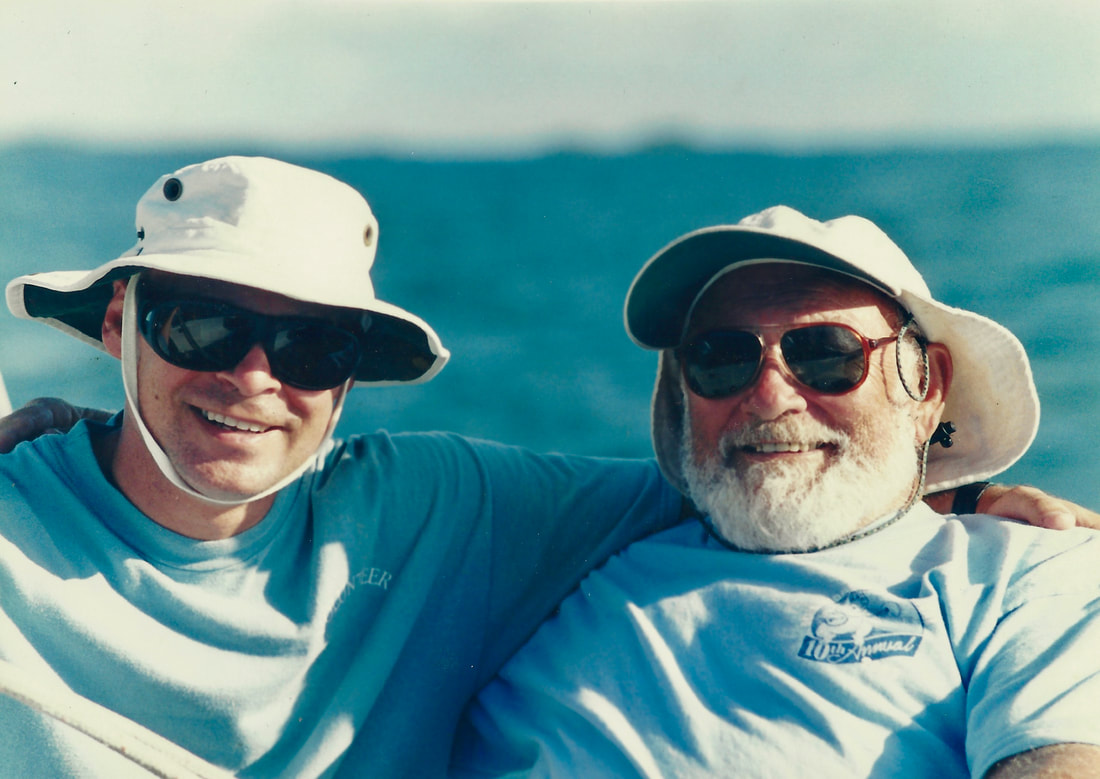

The reason? Dad was more or less forced to save, while Deb was mostly on her own. That’s because Dad was part of a defined benefit retirement plan while Deb had a defined contribution plan. The two terms may sound esoteric, but if you’re in your working years, you ignore them at your peril. For much of the 20th Century, millions of Americans worked for companies or other entities with defined benefit plans. Such plans are typically referred to as pension plans, and nowadays they’re almost exclusive to government entities and a few extremely large corporations. Here’s how they work: My dad was an administrator at the South Carolina School for the Deaf and the Blind. As such, he was an employee of the South Carolina government and was required to participate in their defined benefit retirement plan. Under the plan, a certain percentage of the employee’s paycheck is taken out and added to the overall state retirement fund. That giant fund is invested and managed in such a way that it funds the retirements of all participant retirees. Here is how it looks from the employee’s perspective: You work for the entity for 25 or 30 years, contributing to the retirement fund with every paycheck. This happens automatically whether you plan for it or not. The state contributes as well. Upon retirement, you’re guaranteed a certain percentage of your ending salary based on a formula—typically 60% of the highest salary earned. This is a gross oversimplification in several ways, but you get the idea. The new retiree is guaranteed an income for life, complete with cost-of-living increases to keep up with inflation. In Dad’s case, the state of South Carolina was on the hook: if the state retirement fund ran a little short, the taxpayers would have to cough up the difference. Defined benefit plans are the norm for governmental entities, and they were once common at most large corporations. But they fell out of favor a few decades ago as corporations began shifting the burden of retirement to employees. Under a defined contribution plan, each employee decides how much to save toward their own retirement—and also where to invest that money. Your retirement lifestyle will depend on how much you can accumulate before they give you the proverbial gold watch. Unfortunately, most folks don’t save nearly enough. For the most part, we spend what we make on food, clothing, shelter, cars, taxes, college for the kids, and the occasional vacation. In the 21st-Century economy, that doesn’t leave a lot to set aside for retirement. You may be wondering about Social Security. It is separate and apart from your retirement plan, so most people will collect it regardless. But Social Security is not a retirement plan--just a stopgap to keep seniors out of poverty. To make things worse, financial education is pretty much nonexistent in our schools. And the business models of most financial advisors focus on clients who already have built substantial wealth, which means that Americans with the greatest need for sound financial advice—those in their prime earning and saving years—are pretty much on their own. Fortunately, this problem is beginning to be addressed by a new generation of financial advisors focused on helping younger earners and their families. It breaks my heart to say that if you are one of those older workers who sees no way to retire, I probably don’t have a lot to offer you. But each situation is different, so it might make sense for you to talk with a fee-only financial advisor to explore whatever options you might have. So, how could my dad have had more money in retirement than when he was working? For one thing, he and Mom (also a SC state retiree) had less in the way of expenses. Their four kids were finally grown up and self-sufficient, their house was finally paid off, and their retirement checks automatically rose each year with the cost of living. So despite the fact that their careers didn’t make them rich, their retirement was secure and happy. They also had the satisfaction of knowing that they'd helped thousands of young people make their way from childhood to adulthood. That’s a form of wealth you can’t put a price on. If you’re young and just getting started, those are two good reasons to consider becoming a teacher. Andy Millard, CFP® is a retired financial planner and former principal of Millard & Company, an investment management firm. He does not offer financial planning services; this column is not intended as advice but rather education, commentary and opinion. Consult a professional advisor. If you have general questions about financial planning or investments, feel free to submit them to Andy at andy@andytheadvisor.com.

1 Comment

Michael Brogan

4/19/2021 07:39:23 am

Great post, Andy!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorAndy Millard, CFP® Archives |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed